Hadith Notes

@Hadith_Notes

Hadith Studies | Arabic Manuscripts | Translations of Classical Islamic Literature | The Bukhārī Project | Instructor @qalaminstitute

That concludes my posts on marginal glosses. I explore the topic of ḥāshiyas in more detail in my new paper by Islamic Law and Society (Brill): “Hidden in the Margins”—on the intellectually rich hadith ḥawāshī in 19th-century India. brill.com/view/journals/…

To date, the most rigorous study on Imām al-Bukhārī’s life and the compilation of his Ṣaḥīḥ is Aḥmad al-Aqṭash’s Qiṣṣat Ḥayāt al-Bukhārī (@aktash111). I reviewed the book for AJIS, covering its strengths, highlights, and limitations. ajis.org/index.php/ajis…

Imagine thinking hadith scholars needed the HCM to catch historical inconsistencies. Abū Ḥātim al-Rāzī and Imām Aḥmad would’ve just called that… anachronistic.

Hadith scholars make the HCM look like child’s play. As a simple example, Imam Muslim tosses a hadith. Why? Two solid reasons: it clashes with stronger reports and its narrator stands alone pace trusted peers. Then Muslim lays out "his critical method," systematic and testable.

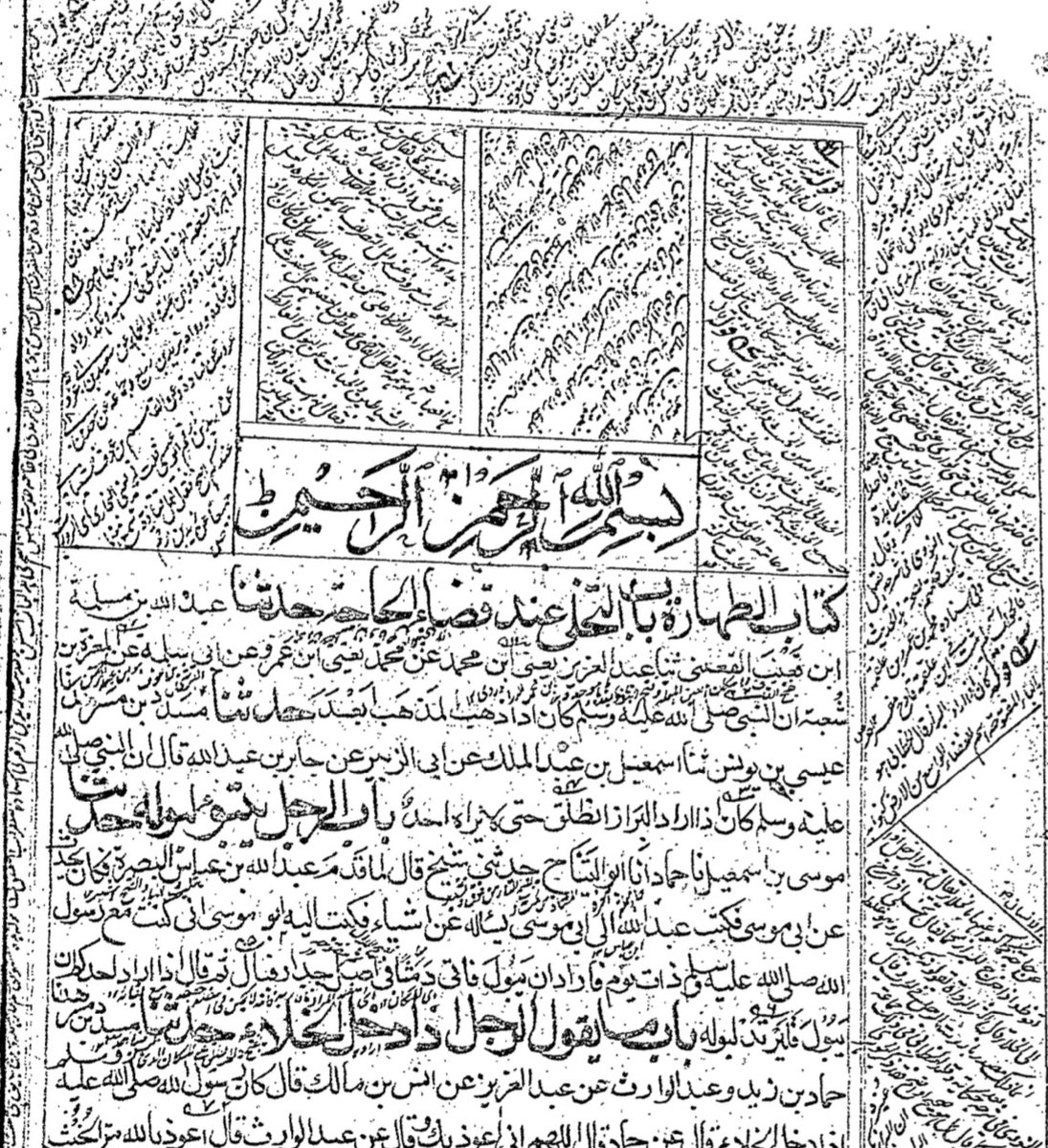

A manuscript's cover page is always fascinating to read thanks to the scattered notes left by the many individuals who handled it over the centuries. In a sense, it's an open scholarly canvas (a kind of intellectual graffiti wall) constantly updated with random fawāʾid.

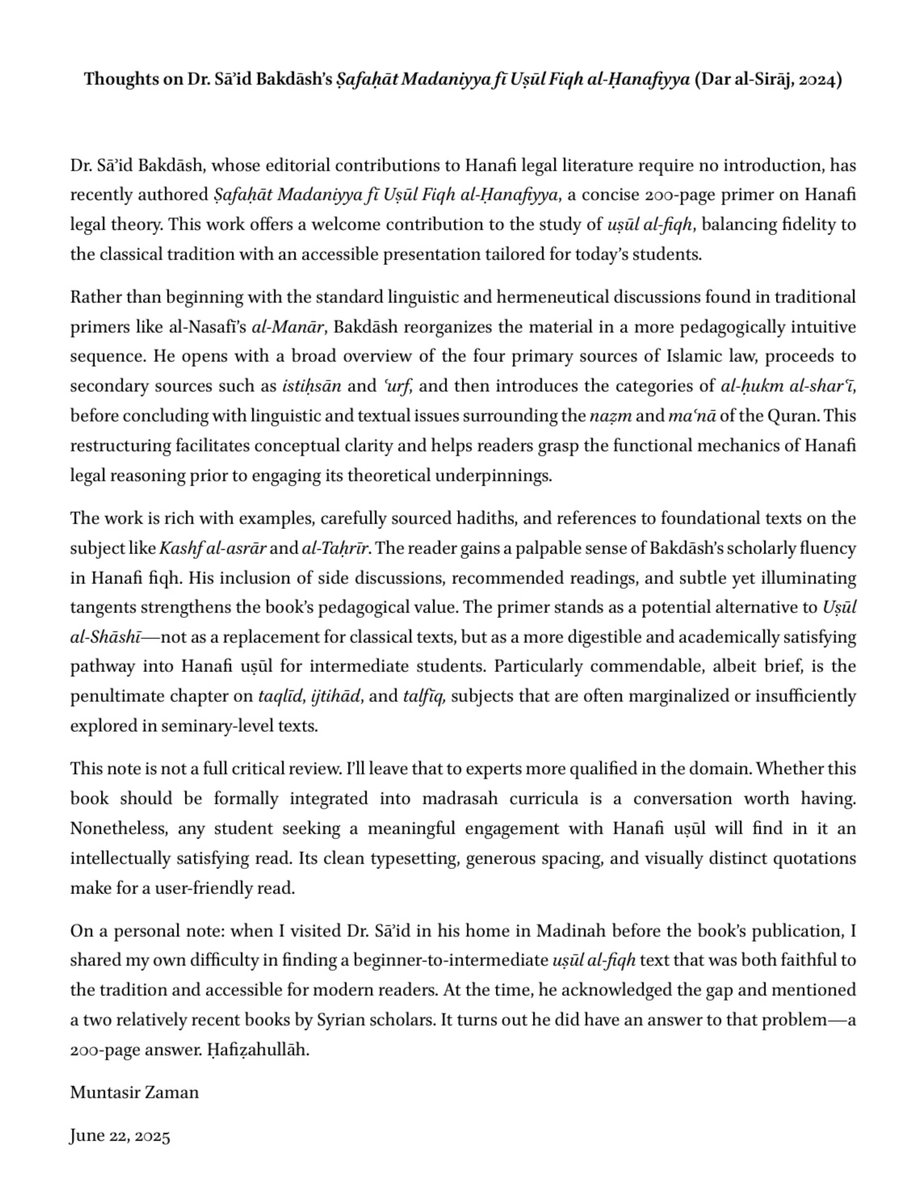

Just finished a quick read of Dr. Sāʾid Bakdāsh’s new primer on Ḥanafī Uṣūl al-Fiqh. Concise, accessible, and ideal for beginning to intermediate students. A welcome contribution from a leading editor in the field. Here are a few reflections:

Reading Siyar this morning, I came across two noteworthy tangents by Dhahabī in the entries of ʿĀṣim and Qatāda: 1. A scholar can be a specialist in one field yet a novice in another. 2. Someone with an overall strong track record should be excused for certain flaws.

Suyūṭī was so offended by Qasṭallānī’s alleged plagiarism that when the latter showed up barefoot and bareheaded to make amends, Suyūṭī responded, “You’re forgiven!”… through a firmly shut door. Forgive? Sure. Forget? Tough.

Interesting to see two major Mamluk-era historians disagree on the conflict between historical reports and empirical data: 1. al-Maqrīzī (d. 845 AH) defends the transmitted reports about human giants, 2. Ibn Khaldūn (d. 808 AH) rejects them as myth, privileging observation.

Here's a paper that I published on dealing with the conflict between Hadith and empirical data in the Journal of Islamic Sciences (CIS).

While Delhi is regarded as the center of ḥadīth scholarship in the subcontinent—thanks to Shāh Waliullāh—an equally vibrant hadith nexus emerged from Sindh and Gujarat (via Ḥijāz). Ṭāhir Paṭṭānī and Ḥayāt Sindī were a drop in the Indian Ocean scholarship from the 15-1850.

Like Abul Ḥasan Sindī before him, Aḥmad ʿAlī Saharanpūrī (d. 1880) was the most prolific hadith muḥāshshī in the 19th century. Alongside critically editing texts, Saharanpūrī wrote insightful ḥawāshī on several ḥadīth compilations—read by millions of students to this day.

In the late 1800s, Shihāb al-Dīn al-Marjānī (d. 1889) had already observed that the Muṣḥaf now held in Tashkent was not an original ʿUthmānic codex—by comparing its orthography (rasm) with early historical records. Philological criticism at its finest!

ʿAbd al-Ḥayy Laknawī (d. 1886) was one of the most accomplished scholars of the 19th century. Beyond phenomenal memory, what helped him develop his rare polymathic skills? In his own words, simple: the Protégé Effect (aka takrār)—teaching a subject after studying it.

In the 19th century, Punjab saw the emergence of significant Ḥadīth scholarship. Two obscure Punjabi scholars in particular produced impressive Ḥawāshī on the Sunans of Abū Dāwūd and Ibn Mājah: the Ḥanafī M. Bārakallāh (d. 1893) and the Ahl-i Ḥadīth Jīwān 'Alawī (b. 1869).

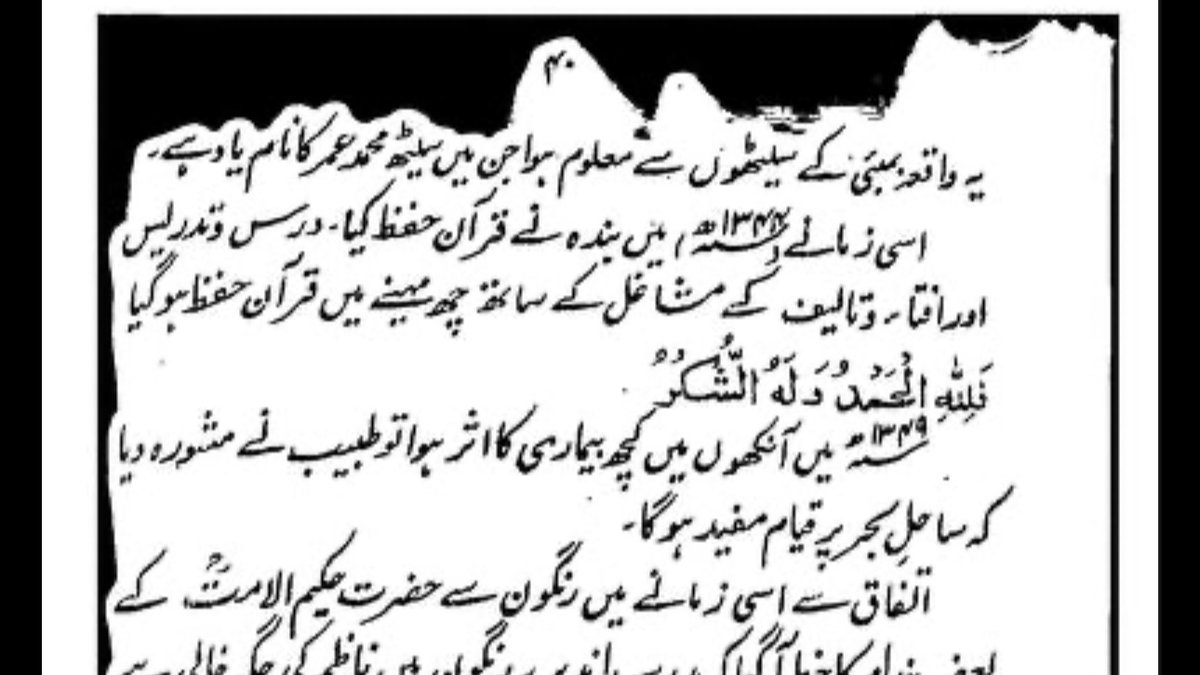

At the age of 34, Mawlana Zafar Ahmad Uthmani memorized the entire Quran in just six months—all while teaching, writing books, and leading the Iftaa department. Where there’s a will, there’s a way!

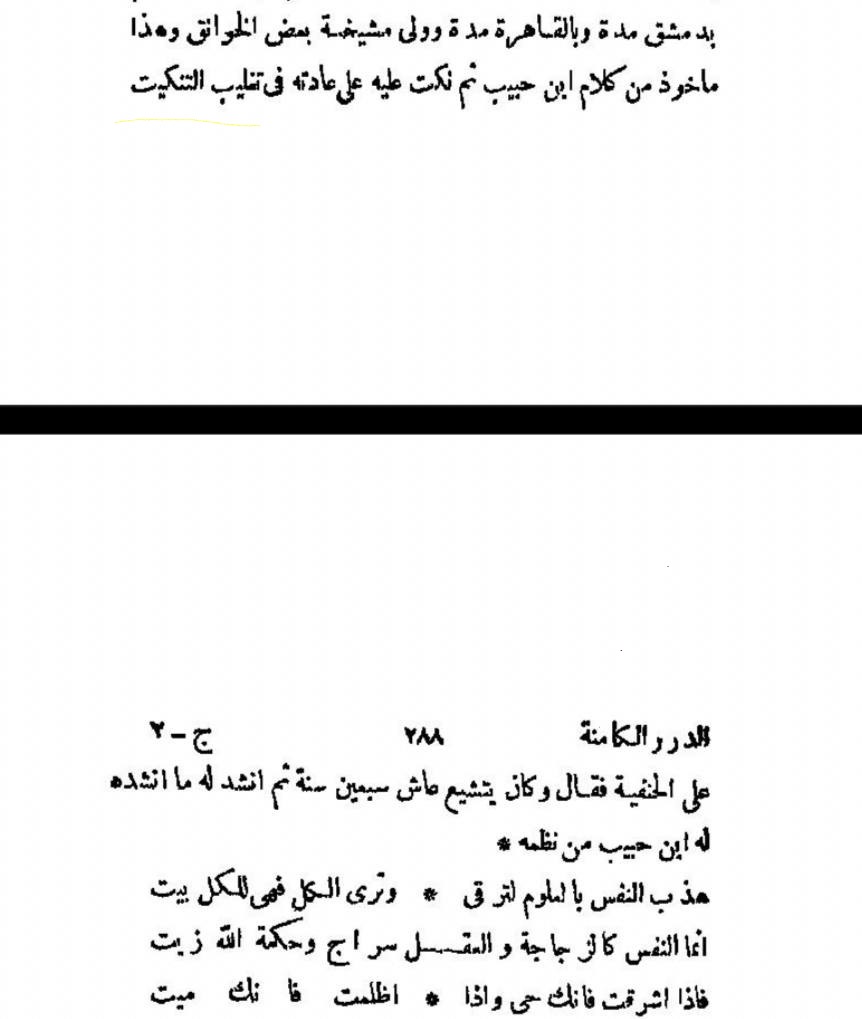

In a posthumous insertion to al-Durar al-Kāmina, al-Sakhāwī candidly admits that his teacher Ibn Ḥajar had a knack for nitpicking the Ḥanafīs. You don't say.

During the last ten nights of Ramadan, al-Maridini completed a recitation of Sahih al-Bukhari at Masjid al-Aqsa for fourteen consecutive years until 913 AH!

The ḥāwāshī on 19th-century hadith collections in India are an overlooked locus of commentarial activity—eclipsed by 20th-century works like Tuḥfat al-aḥwadhī, Badhl al-majhūd, etc. The contributions of Laknawi, Jīwan, & Sahāranpūrī are hidden, quite literally, in the margins.

A striking feature of lithographic print is its preservation of the marginal ḥāshiya—unlike movable type with notes placed at the bottom. Here's Shāh Isḥāq’s (d. 1846) ḥāshiya on the first lithographed hadith text, Sunan al-Nasāʾī—indistinguishable from a classical ḥāshiya.